A data-driven exploration of the evolution of chess: Game lengths and outcomes

Published on May 24, 2014 by Dr. Randal S. Olson

chess game draw expert first-move advantage history of chess stalemate

5 min READ

For the second in my series of blog posts exploring a data set of over 650,000 chess tournament games ranging back to the 15th century, I wanted to look at how chess has changed over time. Nobility and scholars alike have played chess for over 1500 years, and chess has changed considerably since its inception in the 6th century AD. Since I only have reliable data on chess games from 1850-2014, I'll start this analysis at 1850.

Chess has been revolutionized several times since 1850. 1851 marked the first international chess tournament in London, leaving the German Adolf Anderssen as the official best chess player in Europe at the time. The 20th century saw several breakthroughs in chess theory as chess players began to treat chess as a science more than a pastime. With the advent of computers in the mid-1900s, chess players started analyzing games and writing computer opponents to hone their craft. Then in the 1990s, the widespread adoption of the Internet allowed players to play chess games with anyone in the world online.

[caption id="attachment_4235" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Magnus Carlsen represents the newest breed of chess players to revolutionize the chess world.[/caption]

Magnus Carlsen represents the newest breed of chess players to revolutionize the chess world.[/caption]

That leaves us to wonder: How has chess changed in that timespan? In this post, I'll look at game lengths and outcomes over time. In future posts, I'll look at how openings and strategies have grown and waned in popularity over time.

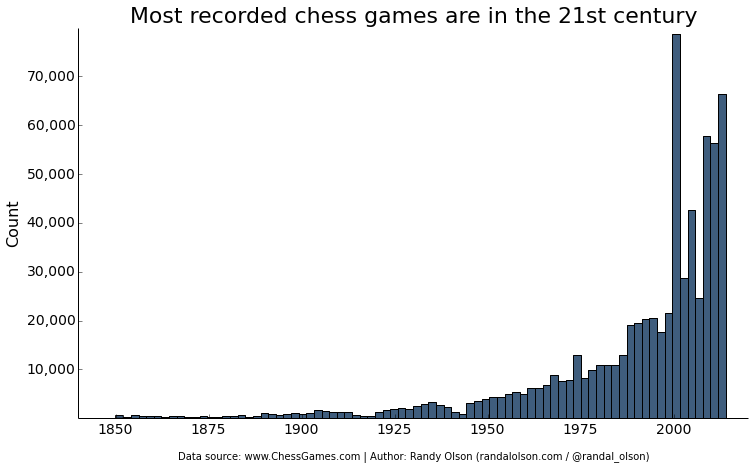

Distribution of recorded chess games

We'll start again with some diagnostics. Unsurprisingly, this data set contains far more games from the past 20 years than for the rest of time. It's becoming easier and easier to keep long-lasting records of chess games now, so we can only expect this trend to continue. Sadly, this means that many games in the 20th century and earlier are lost to us -- but we'll work with what we have. Despite these shortcomings, this data set includes many of the most famous games in chess history, including The Immortal Game and Fischer's Game of the Century.

Chess games are getting longer

The first thing I wanted to look at is whether games have changed in length. My assumption was that due to their extra practice with computers and solid training in chess theory, modern chess players would be much more efficient at closing a game early. The data shows the exact opposite: 21st century chess games are longer than 19th century games. Chess games have in fact steadily become longer since 1970, increasing from 75 ply (37 moves) per game in 1970 to a whopping 85 ply (42 moves) per game in 2014. Furthermore, if the current trend holds, chess games will only keep getting longer as time goes on.

(Note: In all of the following plots, the white line is the mean and the shaded blue area is the 95% confidence interval.)

This trend could possibly be telling us that defensive play is becoming more common in chess nowadays. Even the world's current best chess player, Magnus Carlsen, was forced to adopt a more defensive play style (instead of his traditional aggressive style) to compete with the world's elite.

The first-move advantage has always existed

In my previous post, I discovered that the first-move advantage becomes more pronounced the more skilled the chess players are. When we look at the ratio of White:Black wins in non-drawn games over time, we find that there has always been a first-move advantage: White consistently wins 56% and Black only 44% of the games every year between 1850 and 2014.

It's quite interesting that despite 150+ years of revolutions and refinement of chess, the first-move advantage has effectively remained untouched. The only way around it is to make sure that competitors play an even number of games as White and Black.

Draws are much more common nowadays

Since the early 20th century, chess experts have feared that the over-analysis of chess will lead "draw death," where experts will become so skilled at chess that it will be impossible to decisively win a game any more. The plot below seems to support their fears: Only 1 in 10 games ended in a draw in 1850, whereas 1 in 3 games ended in a draw in 2013. The small dip in draws since 1980 looks promising, but it could very well just be noise.

Former World Chess Champion José Raúl Capablanca proposed a more complex variant of chess to help prevent "draw death," but it never really seemed to catch on in the tournaments. We're now only left to see whether the computer-aided analysis of chess will push us ever further into a sea of drawn games.

So there we have it. This post has given us a high-level look at how chess has evolved since 1850. The first-move advantage has always been an unfair advantage in chess, and chess games are taking longer to conclude and ending in draws more often than 100 years ago. It will be interesting to check in on the state of chess a decade from now to see how these trends hold up.

What else can we learn from this data set? Leave your suggestions and explain why it'd be an interesting analysis in the comments.