Bigger groups make better decisions

Published on May 18, 2013 by Dr. Randal S. Olson

collective intelligence decision making wisdom of the crowds

6 min READ

In his seminal work in 1907, Vox Populi (The Wisdom of the Crowds), Sir Francis Galton looked at the results of a weight-judging competition where participants had to guess the weight of an ox for a monetary prize. As would be expected, there were a wide range of guesses, some of which were wildly inaccurate. Much to his surprise, however, when he pooled the guesses of all 787 participants together, the crowd guessed the ox's weight nearly perfectly.

From apes to ants, animals make better decisions when they work in groups than when they're own their own. What is it about working in groups that makes us perform better? In a paper published this year in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Dr. Max Wolf and colleagues present one way that bigger groups can make better decisions.

We know that animals make better decisions in a group than by themselves, but we're still trying to find out why.

Harnessing collective intelligence

In their paper, Accurate decisions in an uncertain world: collective cognition increases true positives while decreasing false positives, the authors explain that groups can harness each members' unique perspective on a problem by following a specific decision-making process. First, the group members must examine the problem themselves and secretly vote "yes" or "no." (In the paper, "yes" or "no" indicates whether they saw a predator in a picture.) Next, the group members must pool their votes and vote for a second and final time, but this time they vote "yes" only if a sufficient fraction of group members also voted yes, called the quorum threshold. The result of this decision-making process is shown in the figure below.

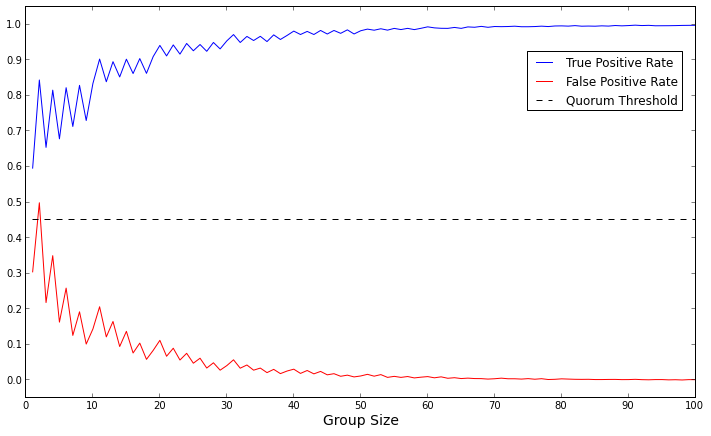

Bigger groups make better decisions: Adding group members increases true positives (accurate "yes" votes) while decreasing false positives (inaccurate "yes" votes).

In this model, each group member by themselves votes "yes" correctly 60% of the time (true positive) and votes "yes" incorrectly 30% of the time (false positive). This means that, by themselves, each group member will perform pretty poorly. However, when they follow the decision-making process described above, a group with 65 members can improve their accuracy to nearly 100%! How's that for the wisdom of the crowds?

Since the authors didn't include the code with their paper, I hacked together a quick version of the model and put it up on Github. Feel free to copy and reuse it as you like.

Now, you may be wondering: "How the heck does that work?" How do otherwise mediocre decision makers make near-perfect decisions when they work together? Unfortunately, the authors don't go into detail on the why of this decision-making process, which no doubt means that will be the focus of future work.

What the paper does explain, however, is the importance of the quorum threshold value. If you play around with the quorum threshold value in the model I linked above, you'll quickly find that this phenomenon only occurs when the quorum threshold value is in between the true positive and false positive rates. If you set the quorum threshold value outside of that range, then adding more group members can actually make the group less accurate.

Models are great, but what about the real world?

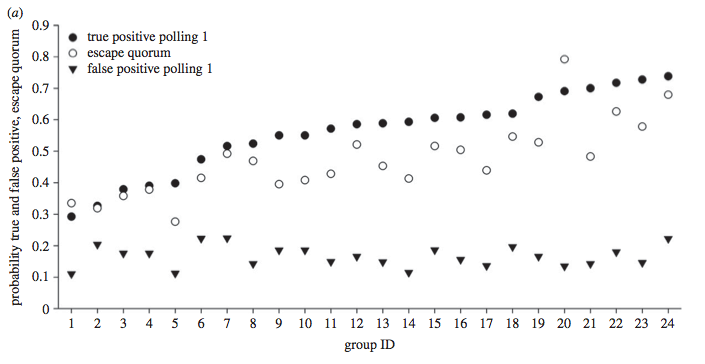

What the authors did next is what really made this study impressive. Knowing that their model predicts the optimal quorum threshold value to fall between a group's true positive and false positive rate, they conducted an experiment with humans to see if this prediction holds up in the real world. Sure enough, shown in the figure below, each group's quorum threshold (labeled "escape quorum") fell in between the group's true positive and false positive rate.

Quorum threshold measured in humans. Figure from http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2777.

The implications of this finding are profound: Not only does having an intermediate quorum threshold increase the efficacy of a group, but it appears that humans are adapted to have an intermediate quorum threshold! It will be interesting to see how this quorum threshold varies across different decision-making tasks. I also wonder if this finding will hold if we measure it in other animal species, or if this finding only applies to humans.

So, what does this mean for me?

All this theory and experimental findings are neat, but what does this mean for businesses, engineers, and the public at large? As it turns out, we all have to make important "yes" or "no" decisions every day. I'll highlight a couple examples from the paper, then add a couple examples of my own. Feel free to add your own examples in the comments.

Doctor

When a doctor examines a patient, they have to decide whether or not the patient has a disease or other ailment. Correctly diagnosing diseases (true positive) while avoiding identifying healthy patients as sick (false positive) is a vital part of a doctor's job. As such, doctors can make better decisions by independently diagnosing a patient, then pooling their diagnoses together to make a final diagnosis.

Search committee

Hiring a new employee can be an expensive and time-consuming process, so it's important to choose the best employee for the position. Search committees can best assess their applicants by assessing each applicant individually before discussing the applicants as a group.

Engineer

When analyzing the blueprints for a building, it is vital for engineers to accurately identify any potential structural faults in the building plans. Thus, design firms are better off having multiple engineers analyze the blueprints independently before holding a meeting to discuss any faults in the plans. Further, it is likely that numerous less-experienced engineers will identify more faults than a single experienced engineer.

I don't know if the reddit designers intended to capitalize on the "wisdom of the crowds" with the reddit model, but there's no denying that they owe their success to it. reddit delivers the most interesting content on the internet because thousands of people are voting on each link, which no doubt leads to an incredibly accurate decision of whether each link is interesting and relevant to the subreddit.

The future of collective intelligence

Decision making lies at the core of nearly every problem we face nowadays. A century after its discovery, there's no doubt that we still have a lot to learn from animal collective intelligence. I hope that we see more research in this field so we can better understand how and why animals work together in groups.

References

Wolf, M., Kurvers, R., Ward, A., Krause, S., & Krause, J. (2013). Accurate decisions in an uncertain world: collective cognition increases true positives while decreasing false positives Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280 (1756), 20122777-20122777 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2777